Each year, both the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and Orange Shirt Day take place on September 30. The day honours the children who never returned home and Survivors of residential schools, as well as their families and communities. Public commemoration of the tragic and painful history and ongoing impacts of residential schools is a vital component of the reconciliation process.

Orange Shirt Day is an Indigenous-led grassroots commemorative day intended to raise awareness of the individual, family and community inter-generational impacts of residential schools, and to promote the concept of “Every Child Matters”. The orange shirt is a symbol of the stripping away of culture, freedom and self-esteem experienced by Indigenous children over generations.

It is also an important time to reflect on the importance indigenous people have had on our culture and society. Included in this, is the impact they have had on the game of hockey.

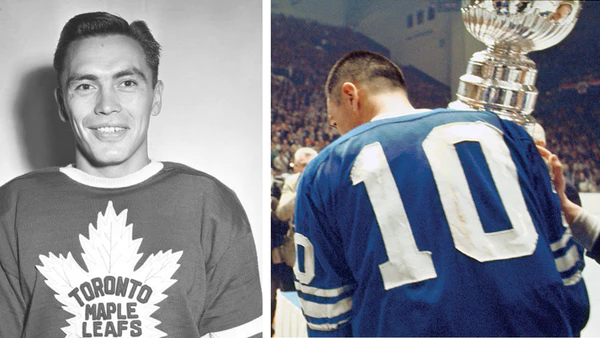

The year is 1967 – The Graduate and The Dirty Dozen are the top films of the year, minimum wage was $1.40 per hour, the common conversation of the day revolved around ‘why is America at war in Vietnam,’ and it was the last time the Toronto Maple Leafs won the Stanley Cup. The captain of that Leafs team, a geriatric bunch with an average age of 31 (the oldest average age of any Cup winner) was their undisputed superstar and indigenous legend George Armstrong.

Armstrong was born in 1930 in Skead, Ontario, to an Irish Canadian father and a Kanien’keha:ka of Wahta Territories mother. The couple were married in Sudbury in 1929 and George arrived eleven months later. He grew up in Falconbridge, Ontario where his father was a nickel miner.

Armstrong developed a passion for hockey but was a poor skater, which his father believed was a consequence of a case of spinal meningitis George suffered at the age of six. Overcome this he did and then some, going on to star for the Toronto Marlboros, then moving on to the Toronto Maple Leafs where he would play close to 1,200 games and amassed more than 700 points.

As great of a hockey player Armstrong is, he is often remembered more for the positive impact he had on the indigenous community. However, carrying the torch and representing his people was easier said and done for Armstrong.

His struggle came from feeling that he could not truly understand the experiences of his community. He was spared from much of the violence and abuse that many others experienced and most of all, he had never had to go to residential school.

His cousin did though and what happened to her is more than anyone, including her, could bear. She was grandmother to Ghislaine Goudreau, who is a professor at Cambrian College in Sudbury. Goudreau’s grandmother and her siblings went to residential school in Spanish and while there, their mother died. They began to spend the summers with their aunt, Armstrong’s mother Alice.

Armstrong saw the effects on his family and though he had certainly experienced racism as a child, it was nowhere near the devastation that affected others in his family. With parents from such vast backgrounds, he struggled with his identity. He referred to himself as a ‘half and half.’

Whether he felt like he fit the role or not, he was a massive role model to indigenous people.

For Waubgeshig Rice, writer and journalist and member of Wausauksing First Nation, Armstrong was that dream that lived in the hearts and minds of millions of Indigenous people.

“Everybody in my community knew who he was,” Rice said. “And I think he’s a big reason why so many Indigenous people especially in Ontario are Leafs fans today.”

Armstrong’s legacy, one which spanned multiple decades, is one of a true gentleman and leader in the sport; something that should not be allowed to fade with time.